Interdisciplinary Science Blog

A Curiosity-Driven, Interdisciplinary Approach to Atoms, Elements, and the Periodic Table

By Jennifer Staple-Clark, Founder and Executive Director

At Slate School, learning is a dynamic journey fueled by student interests and nurtured by dedicated educators who are guided by grade-level benchmarks. Authentic assessment informs our teaching, ensuring a personalized understanding of where each student is in their learning. Classroom activities blend literacy, mathematics, science, history, social-emotional learning, collaboration, and more, creating an engaging interdisciplinary experience.

Our approach to student learning about the periodic table exemplifies our non-siloed, curiosity-driven education. During classroom conversation, our Grade 5 and 6 students expressed interest in chemistry. At the same time, the students were contemplating the organization of information and had been making charts for the plants in their room. This was a natural entre into some key benchmarks in Grade 5 and 6: understanding atoms, their structure and how they interact, the periodic table, understanding and communicating the connectedness of chemical understandings to other scientific fields and other disciplines, and more.

At Slate School, we innovate, and we create our own unique way. Starting in Kindergarten, our students have engaged in exploratory scientific thinking, with a significant focus on environmental science. As our students are moving into molecular and cellular benchmarks of the Upper Elementary years, we continue to avoid mind-numbing textbooks and rote learning. Instead, we are led by children’s curiosities, well-researched and compiled benchmarks, a multitude of books offering a variety of perspectives and lenses, and a whole lot of student wonderings and engagement. Our students consider the historic and scientific basis and significance for the discoveries and information that they are learning, and we always encourage and offer them opportunities to ponder why and how.

Our students began by simply looking at the periodic table, followed by time to write their observations and their wonderings. They shared their thoughts in a whole class conversation, and their wonderings ranged from the numbers represented to why and how the periodic table came to be. This initial conversation led us down many avenues of exploration that were exciting and intriguing to the students.

Students began with what our Grade 5/6 teachers developed and call a “Finger Exercise:” the students think about a quote or image, and write a response for 10 minutes. This is a daily exercise. On this day, students wrote about this prompt: how do you represent something that’s invisible? This led to discussions about invisible atoms and developed into activities where students imagined themselves as 19th-century scientists, selecting elements from the periodic table and creatively representing their atomic structures. Along the way, the students learned how to identify the number of protons, neutrons, and electrons from the periodic table.

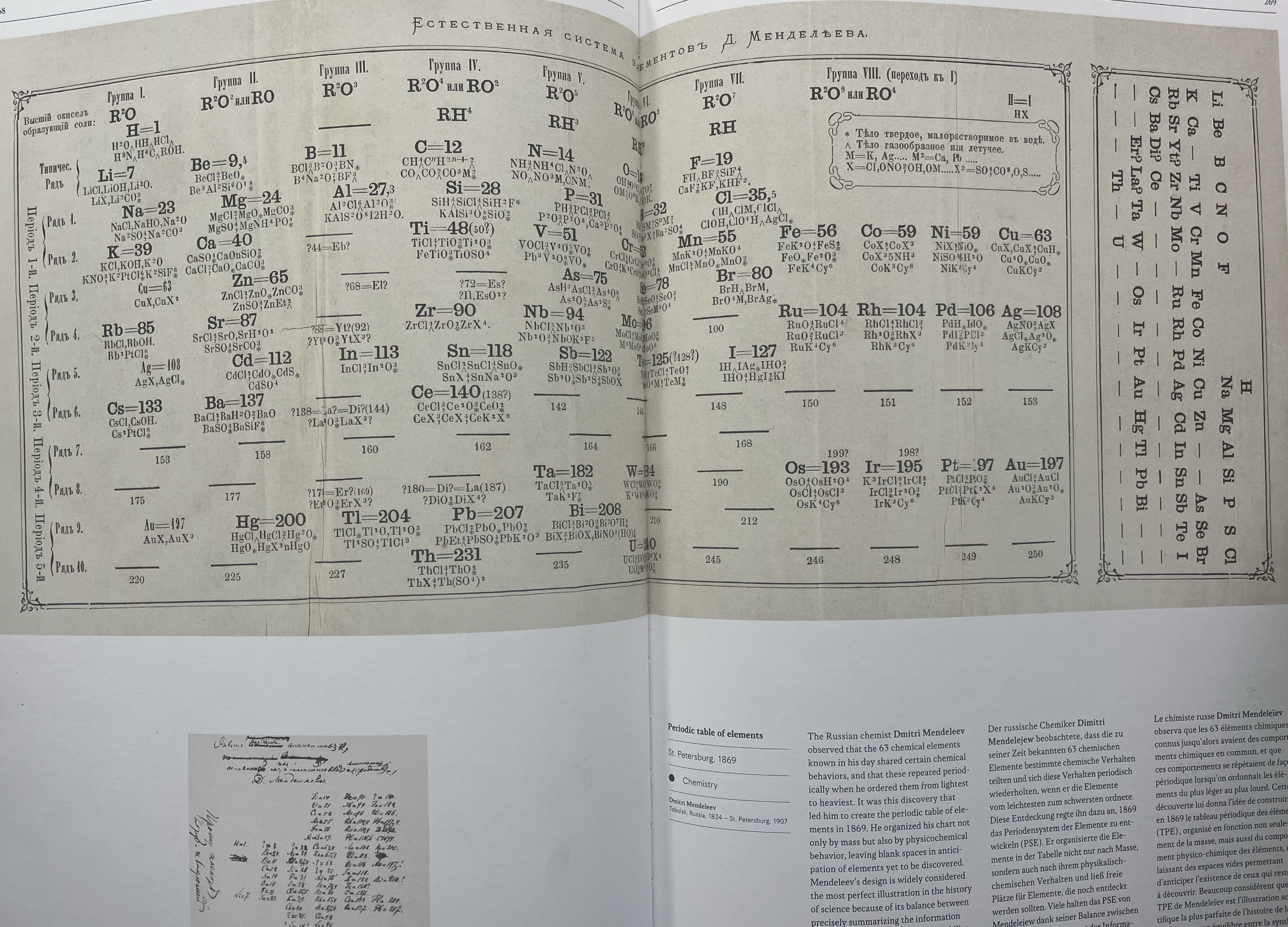

Next, we started thinking about when and how each of the components of atoms (protons, electrons, and neutrons) were discovered, and how the scientific discoveries identified the locations of each within the atomic structure. We thought about Dalton’s solid sphere model of 1803, J.J. Thomson’s plum pudding model of 1904, and Rutherford’s 1911 experiment that discovered the nucleus. Then our students came to realize that Mendeleev created the first periodic table in 1869, which predated the discovery of protons, electrons, and neutrons. We wondered about how Mendeleev organized the elements into a periodic table without knowing about the atom’s components. What information did Mendeleev know and use to create something still being used 150 years later?

The students made observations about Mendeleev’s first handwritten draft as well as the first published periodic table of 1869. One of our students even noticed that his original published periodic table had writing in a different language, and another student who speaks Russian translated the writing for us. We went on to learn that Mendeleev created playing cards where he wrote all of the information that he knew about the 63 elements that were discovered at the time. The students next engaged in an activity in groups where they all had cards resembling Mendeleev’s originals, located the lightest 10-15 compounds based on atomic weight, and then looked for patterns. They sorted the element cards based on weight and oxide pattern, and then by comparing to the periodic table, they deciphered the patterns that Mendeleev uncovered so many years ago.

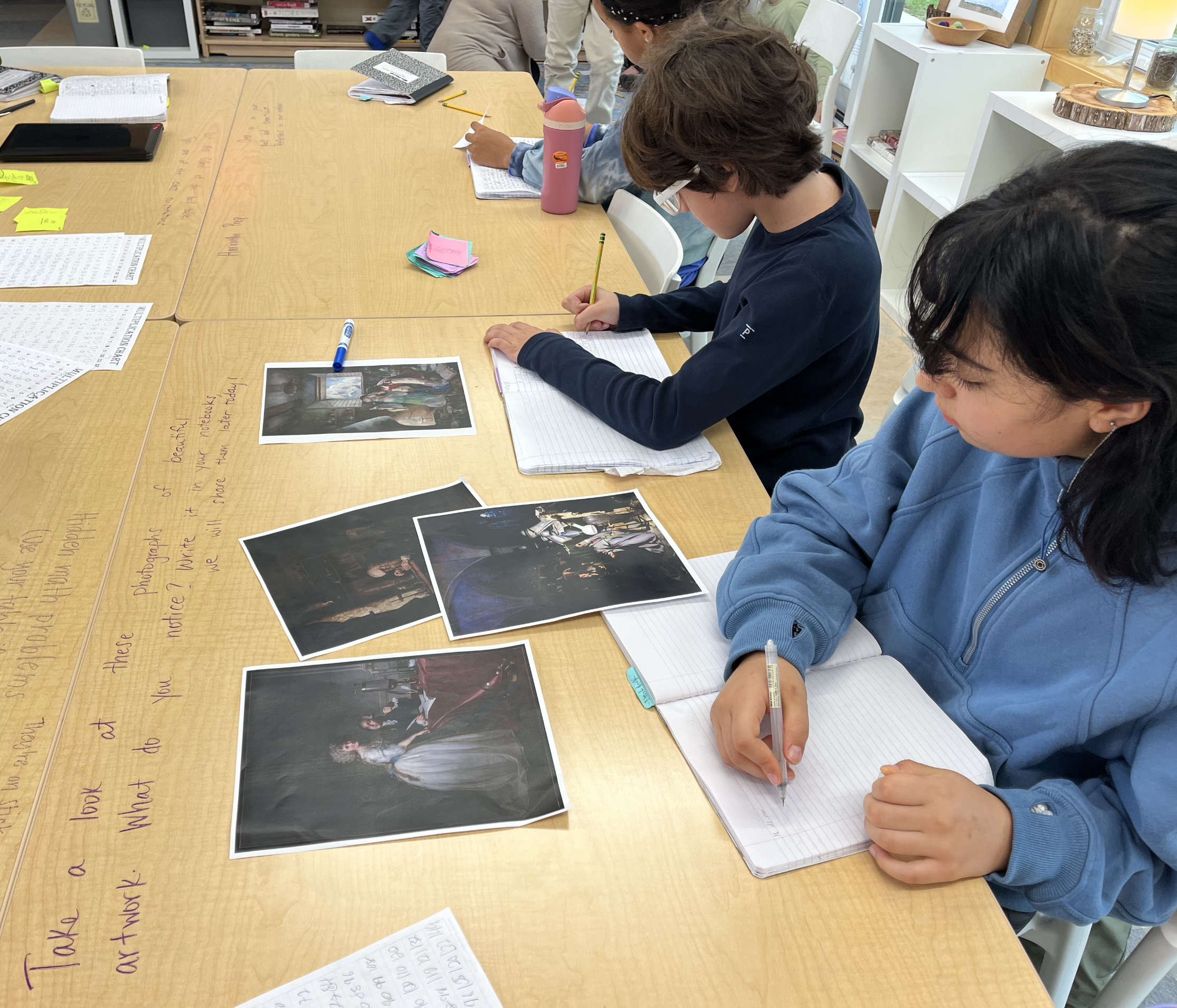

Along the way, students contemplated how the elements themselves were identified. One morning when they arrived at school, one of their Enticement activities was to notice and write about several historic paintings related to the discovery of elements, including The Alchemist Discovering Phosphorus by John Wright of Derby as well as Jacques-Louis David's painting of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and Marie Anne Lavoisier. The students made many observations, ranging from thoughts about the lab equipment being used to the style of their laboratory.

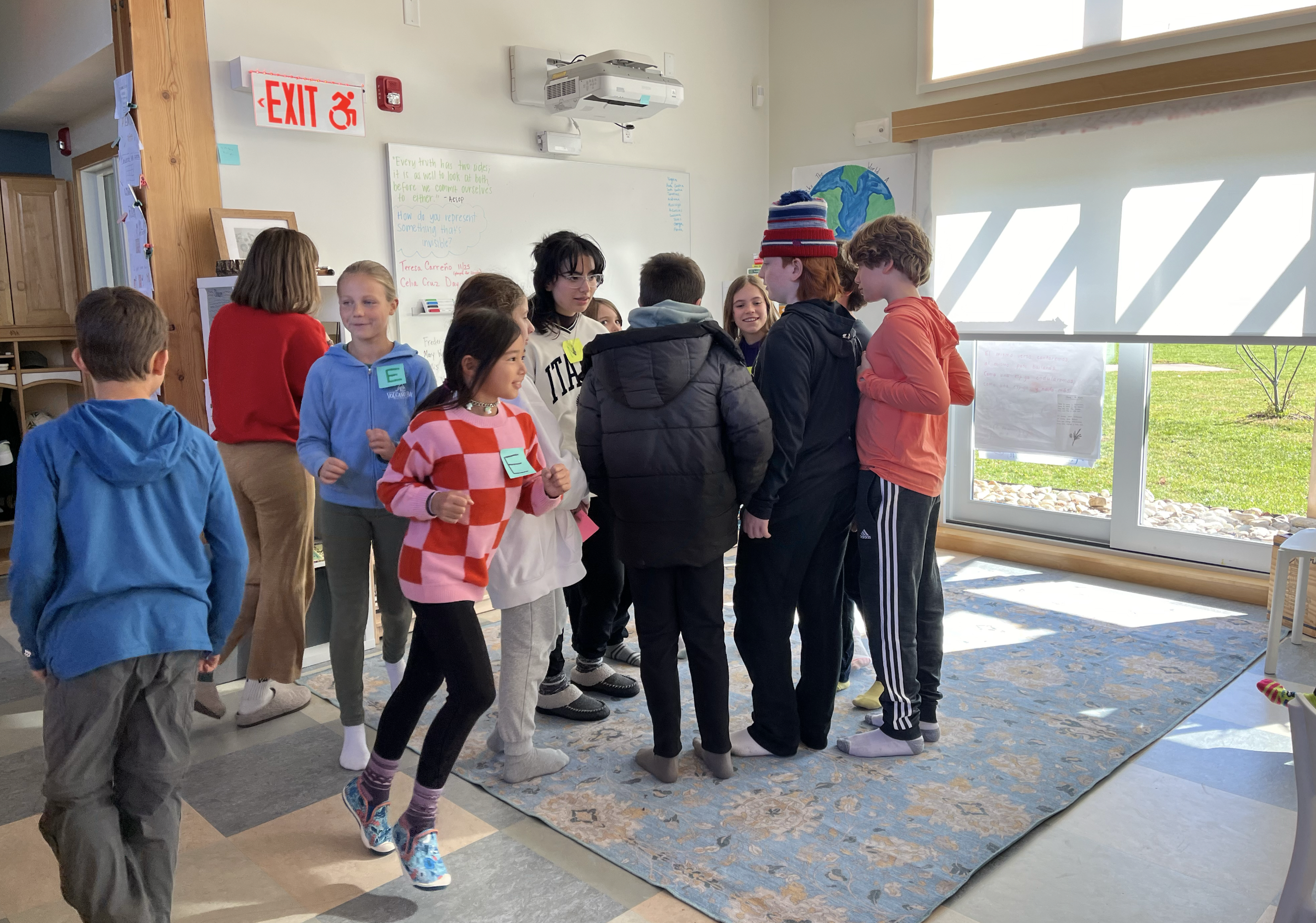

By grounding their learning in the historic scientific process, our students not only absorb foundational knowledge, but also understand how and why scientists uncovered these fundamental principles. Our students were ready to launch into their own investigations of atoms. They learned about electron shells, the number of electrons that fit into each electron shell, and how to organize electrons around the nucleus. As elements were selected and explored, students drew atoms on paper and then collaborated to become the atoms themselves. Some students became protons, others became the neutrons, and others became the electrons, and they organized themselves into the atomic structure for a whole variety of different elements. By noticing the changing electrons for the periods and groups, the students made observations about the patterns of the periodic table horizontally and vertically.

The students have now begun considering compounds as the collaboration of atoms’ electrons. Many of the students connected their understandings of chemical processes and compounds to their independent project topics. Our student studying cooking wondered about the molecular structure of yeast, and then considered the elements that comprise the compound. She noticed that the hexagonal organic molecules in yeast look like honeycombs! Similarly, a student studying diabetes explored the molecular structures of glucose and of insulin, while a student studying cancer looked at the molecular structures of several representative examples of chemotherapy. A student studying Mars thought about the compounds in the atmosphere of Mars and drew the atomic structure and electrons of carbon dioxide.

As our Grade 5/6 students delve deeper into compounds, we anticipate further exciting discovery. Stay tuned for more updates on their evolving interests, wonderings, and understandings.

About The Blog Author, Jennifer Staple-Clark

For nearly 25 years, Jennifer Staple-Clark has been a leader in nonprofit innovation, and she currently leads two nonprofit organizations: Unite For Sight and Slate School. In 2000, Jennifer, who was then a sophomore at Yale University, founded Unite For Sight in her dorm room. Unite For Sight is now a leader both in global health education and in providing cost-effective care to the world's poorest people.

A cum laude graduate of Yale University, Jennifer received a Bachelor of Science Degree in Anthropology as well as in Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology. Early in her career, Jennifer taught high school environmental science and chemistry, where she brought project-based learning to the independent school where she was teaching. She received a national educator award for her work. After dedicating herself to being a high school educator, Jennifer completed two years of medical school at Stanford University School of Medicine before shifting to pursue her passionate interest in global health and eliminating patient barriers to care through building the nonprofit Unite For Sight into an organizational leader in the field. After more than a decade dedicated solely to Unite For Sight, in 2017, Jennifer founded Slate School, an innovative 501(c)3 nonprofit K-12 curiosity-driven and nature-based school in Connecticut. As part of her work as Founder and Executive Director of Slate School, Jennifer draws on her science, medical, anthropology, and public health background to integrate curiosity-driven, interdisciplinary chemistry, biology, and physics into the Upper Elementary classrooms. She is also closely involved in the Upper School interdisciplinary curriculum development.