Curiosity-Driven Projects at the Lower School

The Wonder Seed: Wondering, Learning, and Growing Through Projects

At Slate Lower School, the heart of every day is our work on projects. Beginning in October, each child selects his or her first unique topic of the year. The process, spanning selection to presentation, takes place 4 times in a school year. It is through their interest in these topics that most, if not all, skills are developed.

There is much celebration and great joy as they speak their choices before their entire cohort, and almost immediately, children begin sharing ideas and sources of information with each other. Project topics among the youngest elementary school students at Slate School have ranged from Leonardo da Vinci and Italy to vegetables and fireflies. From the moment that a topic is chosen, each child is considered the expert on their topic. It is both empowering and also a great responsibility that the children take very seriously.

We work side by side with the children to craft open ended questions that they cannot only answer, but also open our eyes to new and wider wonderings. These questions are shared with the families, although we are careful to ask them not to share answers, but rather to wallow in the complexity of their child’s unknowing and “maybes.”

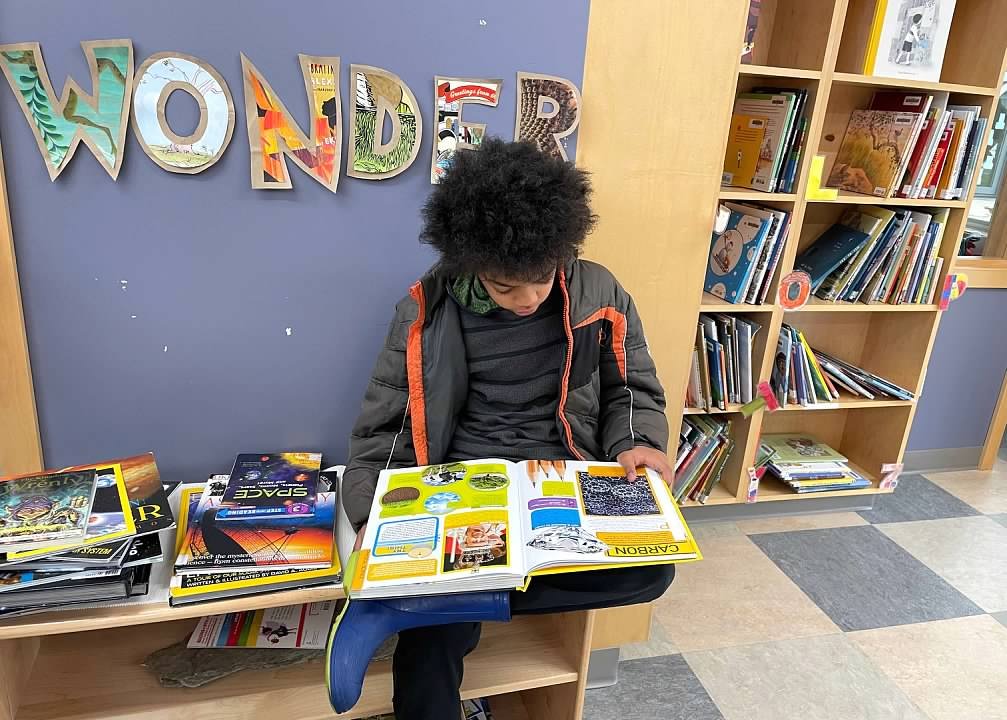

On the day when the books begin to arrive in the classroom, the children are exuberant. They pore over their books with great hunger for learning. We stay in this stage, which we call immersion, for at least a week. They ingest and sort massive amounts of information. The process is almost like that of a lawyer in discovery, where they are reading, filing, and organizing information for later reconstituting in order to satisfy their curiosity and to tell the story of the project.

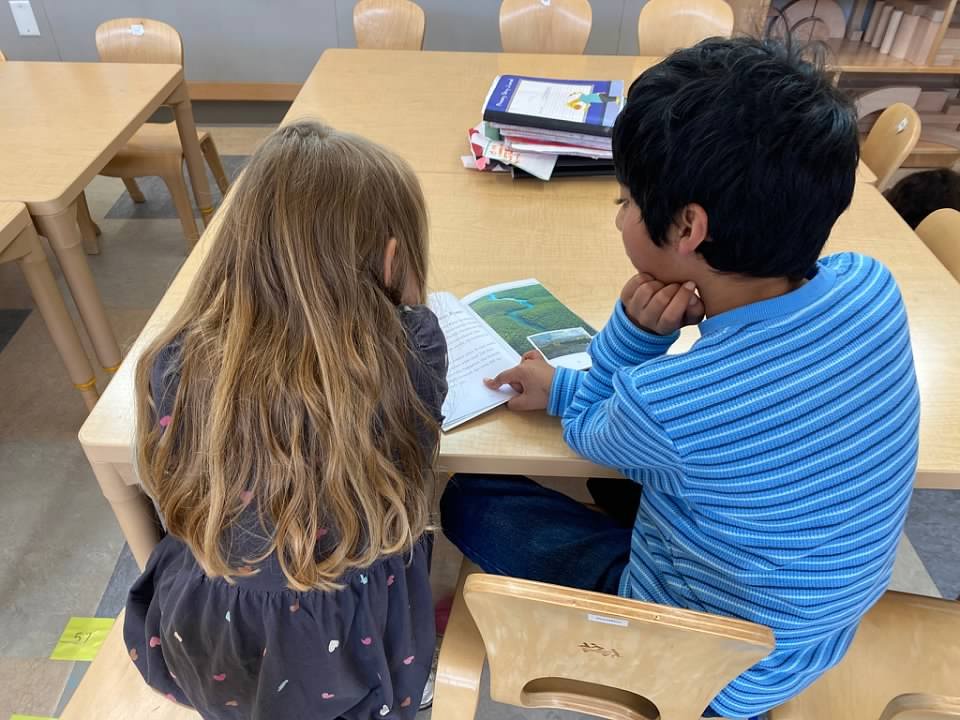

As we enter the next phase of the projects, children are often working hard to build skills around reading more complex texts. They have exhausted the resources at their reading level and are now spending most of their time in project beside a more seasoned reader. They read along, following the text and asking questions for clarification. They also engage in conversation about the information they are hearing. They listen and prioritize information to summarize, or quote. They fill notebooks with impressions, drawings, facts, and more questions. This is the point when the growth is at its most obvious. The learner is actively solving and collecting a text-specific vocabulary, making mathematical connections that can be reflected in text features, and beginning to make connections to other student’s topics.

Collaboration emerges as students share crossover information with each other and build theories to address questions. Teacher and child operate as co-learners, sharing strategies and building skills to support inquiry. Daily conferences include targeted reading instruction, statistics within a wider mathematical context, historical timelines, current relevance and application of new findings, as well as connections with local experts and peer partners.

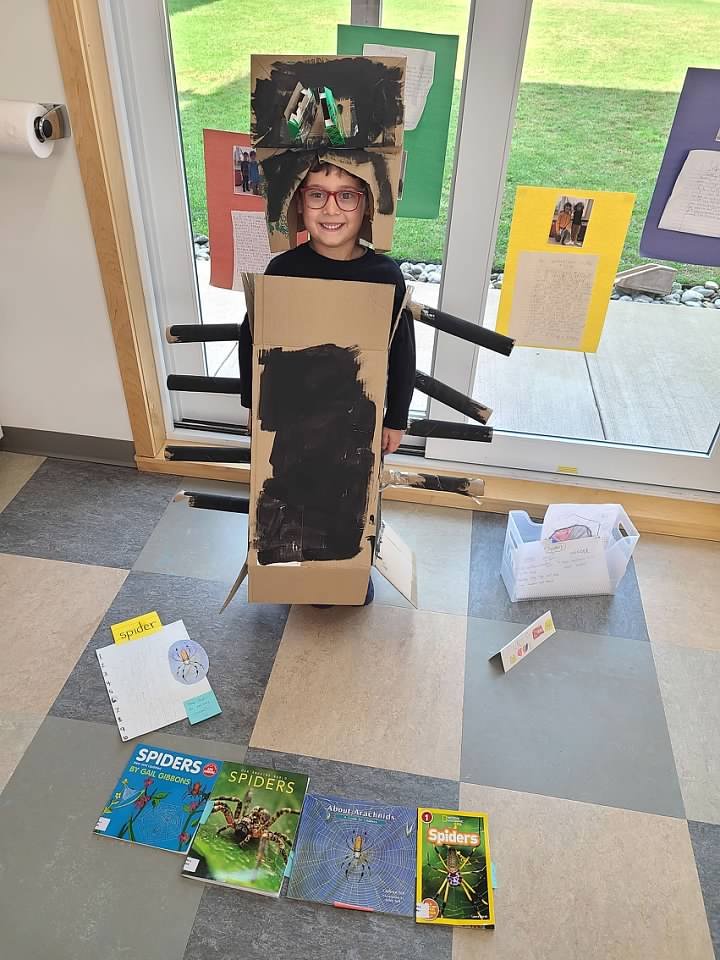

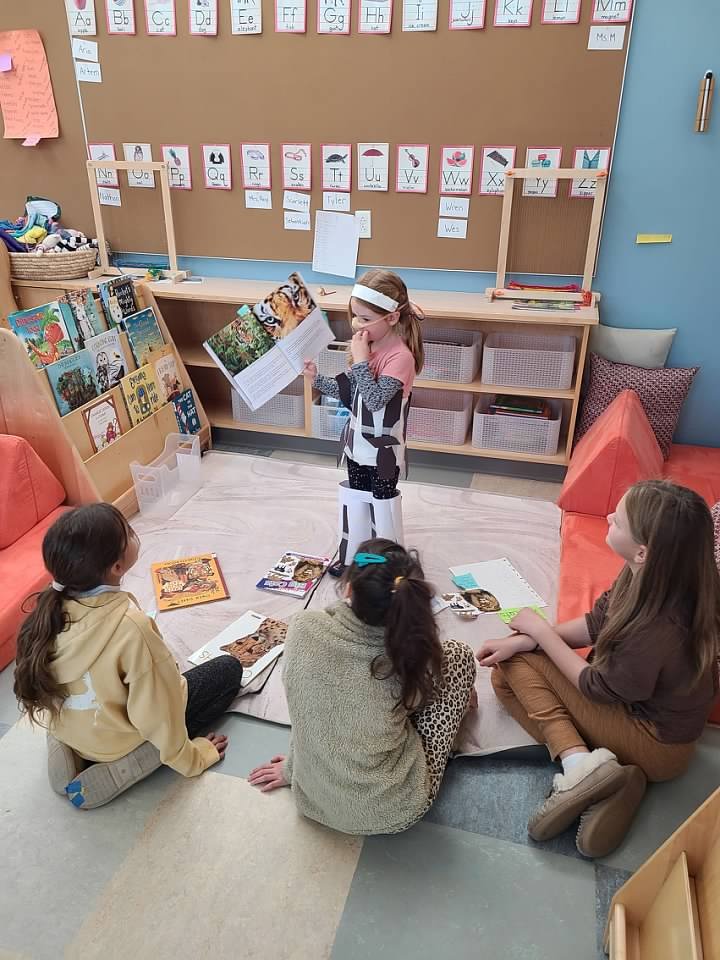

The transition to sharing knowledge begins with the child. Teachers begin to see a change in the conversation at meetings. Children typically begin to zoom out for a wider lens view of their topic. Guidance from teachers turns to the process of draft, revision, and publishing. This process is applicable to all forms of communication. Using notes and artifacts that the child has collected over the course of the study, researchers sort, classify, and prioritize information using strategies taught through direct instruction and modified on a student-by-student basis. Once the ideas are clear, drafting begins. Mentoring during this period may consist of lessons around music composition, foreign language writing, playwrighting, dance, oral reporting, as well as the written word, including informative form, creative non-fiction, and poetry. When first drafts are complete, students share within their cohort and with mentors. Conversation around revision and editing leads to final drafts and then to the final step of preparation for presentation.

At the conclusion of the project cycle, we ask the students a series of questions to better understand the effects of project work on their progress. These interviews are compared only to the student’s other interviews, and we seek to see where the growth is most evident in each cycle.

This project process is altogether joyful, even when it requires perseverance. It is fruitful, even when we stumble, and it is rich even when we exhaust every resource without finding the whole answer to our question. At Slate School, we say that we want our children to innovate, and following their passion for learning is the direct path to innovation.